In a world that is getting smaller every day thanks to the relative ease of migration and the blessings and burdens of technology, it is not unusual for a writer to see himself as an inhabitant of multiple identities at once. We are no longer tied to just one place. In fact, it has never been easier for people to leave their homeland in search of a new life. For writers and thinkers of the 20th and 21st centuries in particular, the traces of migration and movement are markers of what it means to have the fullest understanding of being in the world at that particular moment. In Maxim D. Shrayer’s new book, Immigrant Baggage: Morticians, Purloined Diaries, and Other Theatrics of Exile, Shrayer counts himself among those who have had the blessing or curse of being forced to trade one identity for another. But the question is always whether you ever really leave the remnants of a past identity behind. For Shrayer, the answer seems to be: No, you don’t. For the reader, the proof of this is clear and its traces can be found in each of the stories in this collection.

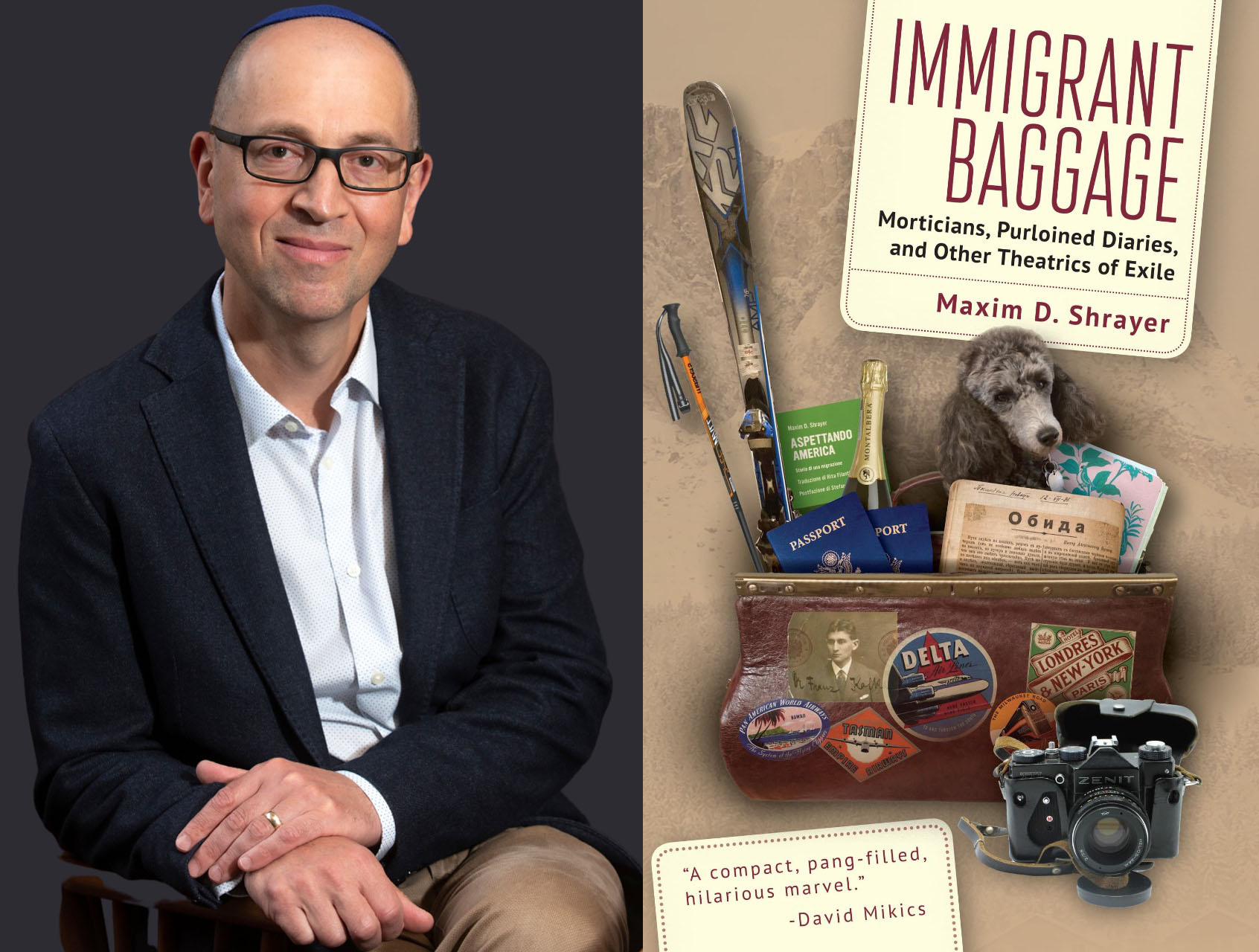

Shrayer is no stranger to the history of exile and migration. And while the ease of travel and freedom of movement may be a sign of our times, it was not ease that characterized the emigration of young Shrayer and his family from Soviet Russia. They spent eight years as refuseniks before finally emigrating to the United States in 1987. In his 2007 literary memoir, Waiting for America, the first book written in English to describe the experiences of Soviet Jews waiting to enter America after their release from Russia, he tells the story of his own coming of age. It is not just a transition into adulthood, but also an understanding of what it will mean to carry the baggage that all exiles bring with them into their new lives.

It is not unusual to write about balancing dual or hyphenated identities; it is also not unheard of to write about leaving one place to move to another and live there as a kind of perpetual foreigner. But Shrayer’s approach is unique in that he sees his experiences—from his origins as a Russian-Jewish child in Soviet Russia, to his time in the pre-immigration Italian detention camp, to his life as a successful scholar and professor in the United States—not as the defining factor of his identity, but as the touchstone of something more crucial. For Shrayer, “writers are not just products of their origins, but also creative makers of their identities.” This realization was “devastatingly brought home to him” by the war in Ukraine, since three of his grandparents were born there, although he says he has always known this and tried to reflect it in his work.

A central question in Shrayer’s book is what it means to write “translingually,” to live in or operate between multiple languages. “Translingualism means more,” he writes, “than working not just in one language but in two or more, simultaneously or successively.” That Shrayer has not simply traded one identity for another is clear in all of his stories. If it is not the American years he spent “under the belt of the Soviets,” then it is the question implicit in each of his trips to his native Russia with his daughters: how can one become something entirely different, adopt a new cultural or national identity, when one has spent one’s most formative years in an entirely different place? Shrayer’s identity, then, is one of movement, of pushing and pulling. Shrayer’s mother, for example, wonders why he returns year after year to the place her family tried to escape, but for Shrayer it is “a return to (his) own childhood and youth – the lost joy of pure friendship. In the wrong place and yet at the right time.” You can’t just give up or discard your childhood just because it is placed in a geographical context. “I was still trapped in the memories of my Soviet years,” he writes.

A central question in Shrayer’s book is what it means to write “translingually,” that is, to exist in multiple languages or to act between them.

Translingual writing is not something static and immobile, but a body full of movement. It is the way of describing a life in “transit”.

Shrayer is a writer who is perfectly aware of himself. At the beginning of “Yelets Women’s High School,” he writes, “The blood vessels of classical Russian literature permeate this story like capillaries permeate the vermilion rim of human lips. And yet the American in me has trouble with a traditional structure,” but as it turns out, “the raw material of life dictates its own rules of storytelling.” A writer’s origins and his literary language are inseparable: another new language created to add to the translingual list. But a life in “transit” is still a life subject to the passage of time. And yet, Shrayer muses, “Only time will tell whether we will lose our Russian-American and Russian-Canadian voices with Jewish accents.”

This accent and the mixing of several languages ultimately constitute the “immigrant baggage” to which the book’s title refers. But as a careful reading of Shrayer’s stories shows, Jews are not the only ones with this baggage.

Shrayer may wax lyrical about “the pleasure of writing in tongues,” but that’s not surprising, since in almost all of his stories he reveals a fascination with detailing the languages and accents of everyone he deals with. The tongue, it turns out, gives it all away. In one story, a woman speaks a “rich, beautiful, slightly old-fashioned Russian,” while in another, the appearance and accent of a German doctor who witnesses a snowboarding accident in which Shrayer happens to be hit by another German doctor leads Shrayer to believe he is a “retired SS man.”

This particular story, “Ribs of Eden,” is actually my favorite story in the collection, not least because I spent a lot of time in the Dolomites and the autonomous region of Italy called South Tyrol in German and Trentino-Alto Adige in Italian, where the main events of the story take place. There are three official languages in this region: Italian, German, and Ladin. But I always feel that German is the preferred language in this part of Italy. The restaurant menus testify to this preference. Instead of the expected pizza and pasta that tourists dream of in Italy, German and Austrian-inspired dishes like Spätzli and goulash are typical here. Not to mention the apple strudel, which, according to my son, is truly the best in the world. The setting is all Alpine-German, but if I speak Italian there, no one bats an eyelid, while every now and then you hear a restaurant waiter speaking a language I don’t understand at all (Ladin): a truly strange and unsettling place.

It is almost ironic that this is the scene of an accident in which Shrayer is hit on the slopes by a German snowboarder, a man with a “frog-skin face so clean-shaven it looked as if it had been splashed with sulfuric acid.” Shrayer notices that the German immediately speaks in English: “You took a wrong turn.” As the elderly “retired SS man” (who turns out to be a perfectly decent person) passes by on skis, he addresses the guilty German snowboarder in German: “I saw everything. All your fault.” The rest of the story concerns Shrayer’s yearning for “general justice” and his negotiations with German insurance companies, which ultimately fail due to “lack of evidence.”

What is clear, however, in this story, which is just one of several snapshots in the book, is the “hidden structure of exile,” the feeling of being inside and outside of a place at the same time. And what about the baggage? In the foreword, Shrayer mentions the few material items they took with them when they left Soviet Russia, but aside from typewriters and some books from the Moscow library, not much of the “material baggage” remains. But “as for the memory of our life before emigration, it took much longer to get rid of the intangible baggage of exile.”