Natalia Alberto

Natalia AlbertoIf José Duval Mata is still alive, he is trapped in a living nightmare.

The 26-year-old tractor driver has been in prison in El Salvador for more than two years on charges of “gang membership,” although the country’s judiciary had already ordered his immediate release twice.

Despite two judges’ clear rulings in his favor, Mr. Mata still languishes in one of the world’s toughest prisons: El Salvador’s notorious Cecot, a maximum-security facility for “detaining terrorists.”

The BBC has repeatedly brought the case to the attention of the government of El Salvador – including earlier this year directly to the public prosecutor, the Ministry of Security, the vice president and President Nayib Bukele himself.

Despite repeated assurances from the authorities that they would investigate the case, no action has been taken so far.

It is a story of Kafkaesque proportions.

In April 2022, Mr. Mata was on his way home in the dusty rural community of La Noria when he was stopped by troops who had entered his village as part of President Bukele’s nationwide crackdown on the country’s powerful street gangs.

Lissette Lemus / BBC

Lissette Lemus / BBCDue to an emergency decree called a “state of emergency,” numerous constitutional rights have been suspended. Police and military can now arrest anyone suspected of gang membership without due process.

In two years, around 70,000 people have been arrested, including about 3,000 children, many of them with no apparent connection to gang activity, says New York-based Human Rights Watch.

Although Mr Mata claimed he had never been a member of or worked for a gang, troops arrested him for “illegal association” – a blanket term used during the state of emergency to round up people.

His mother, Marcela Alvarado, has not seen or heard from her son since that day.

“The police told me I had to bring evidence to prove his innocence, so I collected his school certificate, the title deeds for his land, his repayment receipts for his bank loan and a statement from his employer about his good character,” she explains, showing the BBC the documents that experts say hardly any Salvadoran gang member would possess.

Their efforts were in vain.

José Duval was tried along with more than 350 other prisoners in a mass trial that lasted only a few minutes. He was initially sentenced to six months in prison, which has since been extended indefinitely.

Marcela still cries when she remembers it. But things were about to get much worse.

José Duval was temporarily released after a judge ordered his immediate release in September 2022.

However, he was subsequently arrested again – on the same charges – outside the prison gates while waiting for his family to pick him up.

The renewed arrest of prisoners at the prison gates is “arbitrary measures … illegal detentions and cases of double punishment,” says Noah Bullock, executive director of El Salvador’s leading human rights NGO Cristosal.

Nevertheless, he says, this practice was widespread during the state of emergency.

In June 2023, a second judge upheld the earlier decision to release Mr. Mata. But more than a year later, he is still behind bars and Marcela’s increasingly desperate pleas for information fall on deaf ears.

Natalia Alberto

Natalia AlbertoJosé Duval’s family has now submitted his case to the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights.

A source within El Salvador’s public prosecutor’s office told the BBC that they saw “no legal justification or clear explanation” for the young man’s continued detention.

Throughout the ordeal, Marcela brought a food package every week to the Izalco prison where her son was being held – a plastic bag filled with “cornflakes, porridge, bread and biscuits,” she said, to tide José Duval over and above his meager prison rations.

When she handed him a bag of groceries last June, the guards told her that he had been transferred from prison a few weeks earlier.

Their worst fears had come true.

José Duval was now in Cecot – the Center for the Control of Terrorism – a maximum security prison that is the cornerstone of Bukele’s anti-gang policy.

Mr Bukele’s supporters welcome the facility as evidence of his iron-clad fight against gang violence.

Its critics consider it a black hole of human rights and one of the toughest prisons in the world.

President Bukele has often stated that the inmates see “not a ray of sunshine” and receive only the most basic rations of cold rice and tortillas.

The Bukele government widely published images of shaved-headed and heavily tattooed prisoners being transferred to the facility.

Reuters

ReutersMr Bukele has repeatedly defended the state of emergency and Cecot because they have changed the security picture in El Salvador.

Numerous no-go areas and gang-controlled neighborhoods are actually back under the control of the security forces and entire communities report that they no longer live in fear.

For this reason, the tough approach is so popular. Millions of people in El Salvador are eternally grateful to their young, media-savvy leader for tackling the gang problem with swift and ruthless violence.

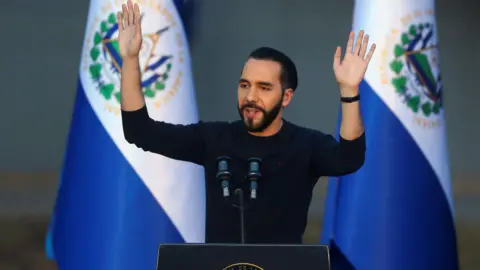

In February President Nayib Bukele was re-elected with an overwhelming majorityand secured around 90% of the votes.

At a press conference, I asked him whether he would focus on releasing those wrongfully imprisoned in his second term.

President Bukele began a long response attacking his critics, especially those abroad, arguing that there had been high-profile miscarriages of justice in the United Kingdom.

His security forces had only made “a few mistakes” and around 7,000 people had already been released.

The rigorous action has restored calm on El Salvador’s streets and that is the most important thing, he stressed.

Reuters

ReutersI told him details about José Duval Mata’s case and after the press conference his team asked me for copies of the judges’ release orders. A few days later, a member of his inner circle asked for the information a second time, this time in digital form, which I again provided to them.

In the weeks that followed, the BBC continued to target the Bukele government, and I spoke directly to Vice President Félix Ulloa several times about the case.

Over a year ago, he told the BBC that Mr Mata was just days away from being released.

Mr Ulloa expressed his hope that the media would portray José Duval Mata as a “symbolic case of due process” after his release from prison.

In fact, he was transferred to Cecot at that time without his family’s knowledge.

Earlier this year, after months of requests, the BBC was granted access to Cecot, but we were not allowed to speak to inmates or question officials about specific cases.

Marcela has not received proof of life or formal confirmation of her son’s well-being for over two years. Not surprisingly, she often thought that José Duval might have died in prison.

“I thought about it all the time,” she tells me from her small plot of land in La Noria. “I was obsessed with the idea, I was completely desperate. I just cried.”

Now, she says, she just clings to the hope that her son is still alive and will be released at some point.

“I trust in God. That’s all I can do.”