Other

OtherGeneral practitioners in England have launched a service-to-rule battle in a dispute with the government over alleged underfunding. This threatens to bring chaos to the system.

Doctors’ offices are taking various measures and some are limiting the number of patients each GP can treat to 25 per day. This could reduce the number of available appointments by a third.

However, since it is already difficult for many patients to see a doctor, there is growing concern that this could pose a risk to patients.

“Turning point”

Dr. Tom Gorman says that participating in the go-slow strike is a last resort, but he feels compelled to do so to protect his patients.

The 41-year-old has been a general practitioner for eight years and says that the System is at the “breaking point”.

“We cannot offer anything to our patients. They are struggling to get appointments. We do not want to do anything, but are forced to protect our patients and employees.”

There is a lot of data to support such claims.

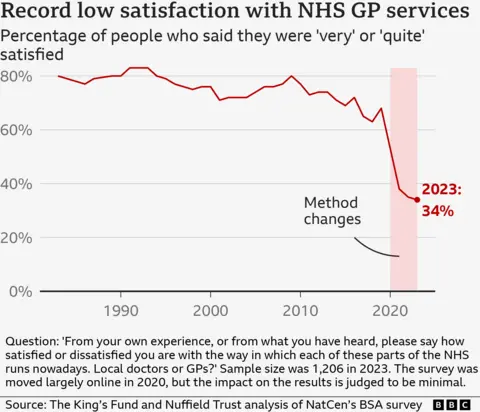

The latest British survey on social attitudes – the gold standard for measuring public attitudes towards the NHS – shows that satisfaction with GPs has reached an all-time low.

Additionally, NHS England survey data One in three people say they feel they have to wait too long for an appointment, and one in five describes their experience of contacting their GP as bad.

Younger adults and people from the poorest areas are particularly dissatisfied.

The range of duty-to-rule options

As a partner in a practice in Newcastle, Dr Gorman has the authority to decide the next steps.

This is because GPs are effectively independent businesses – so this is not a strike or industrial action in the traditional sense.

The British Medical Association (BMA) has proposed that GPs Choose from a range of options.

These include limiting the number of patients treated per day, failing to provide tests and check-ups to hospitals, ignoring rationing policies that could lead to a flood of hospital transfers, and refusing requests to share data.

Dr. Gorman says he and the other partners have yet to decide exactly what steps they will take, but they certainly plan to get involved.

“We are focusing our actions on stopping the immense amount of work for which we are neither contracted nor paid – or whose execution is uncertain.”

GPs believe that this focus is to ensure that working to the rule book does not breach their contract under which they provide NHS services and therefore avoids cuts to their funding.

To illustrate this, Dr. Gorman gives the example of blood sampling and other tests commissioned by hospitals.

“It’s more convenient for patients, but we often don’t get paid for it,” he says.

“We essentially do our job and that of the hospital.”

Dr Samira Masoud, a GP in Kent, agrees. She has spent some time working as a locum in recent years and has been able to organise her working hours freely because the pressures of her job became too great.

“We are expected to treat too many patients, work late into the evening and rush appointments. This is not safe and carries the risk of burnout.

“I treated 35 to 40 patients every day and I simply cannot devote the time they need to them. Limiting the number of patients could significantly improve the situation for both the GP and the patient.”

Affected patients could come off worse

Of course, limiting the number of participants also has the disadvantage that it will be more difficult for all patients who want to see a family doctor to get an appointment.

NHS England warned that the go-slow could lead to more people having to go to emergency rooms to seek help and could have wider impacts on the system, such as delayed discharge from hospital.

And patient protection organisation Healthwatch England believes this could ultimately harm patients.

“Access to a GP is the problem we hear about most often,” says Managing Director Louise Ansari.

“We fear that the go-slow strike could make the problems worse or even discourage people from seeking help at all.

“Any delay in treatment can have a huge impact on people’s physical and mental health.”

Even some general practitioners seem to share this concern.

A snap poll of more than 250 general practitioners published this week by the medical journal Pulse found that one in four believe that working to the letter could cause short-term harm.

However, half of them said they would be willing to continue the go-slow strike indefinitely.

Much now depends on how many family doctors participate.

It is still unclear how many people have been affected since the BMA announced the duty to operate according to regulations at the beginning of August.

It is unlikely that all GPs will get involved – after all, only around two-thirds are union members – and the BMA itself has said it expects this to be a “slow process” with GPs gradually increasing the pressure.

How can this problem be solved?

At the heart of the dispute is money. The previous government announced at the beginning of the year that it would increase funding for primary care by almost two percent.

The BMA did not consider this sufficient and ordered a member vote before the election.

Because the practices are independent, their staff are not directly employed by the NHS, so they were not the trigger for last year’s pay rises that led to strikes by nurses and doctors.

The new government has already announced that it will pump more money into the coffers and Health Minister Wes Streeting has called on GPs to stop working as per regulations.

Dr Becks Fisher, research and policy director at the Nuffield Trust think tank, believes it will take more than a one-off cash injection to put an end to this, as funding has been “lagging behind demand and inflation” for years.

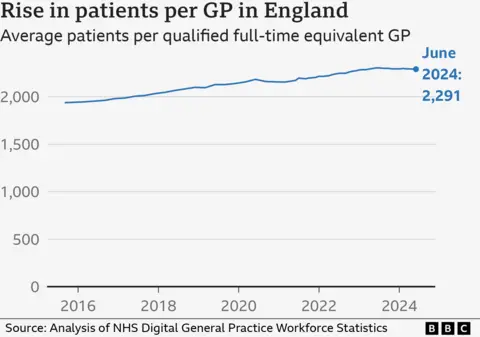

The result? A recruitment and retention crisis. Despite boastful promises to increase the number of GPs over the last two parliamentary terms, the Tories are nowhere near achieving their stated targets.

As a result, the number of patients per GP is increasing and it is mainly the under-30s who are giving up their doctor – precisely the age group on which the future of general medicine depends.

Dr Fisher believes this conflict is likely to continue until the sector is put on a “more stable footing”.

“GPs hate feeling like they can’t provide their patients with the quality care they deserve,” she adds.

Research and data analysis by Hannah Karpel