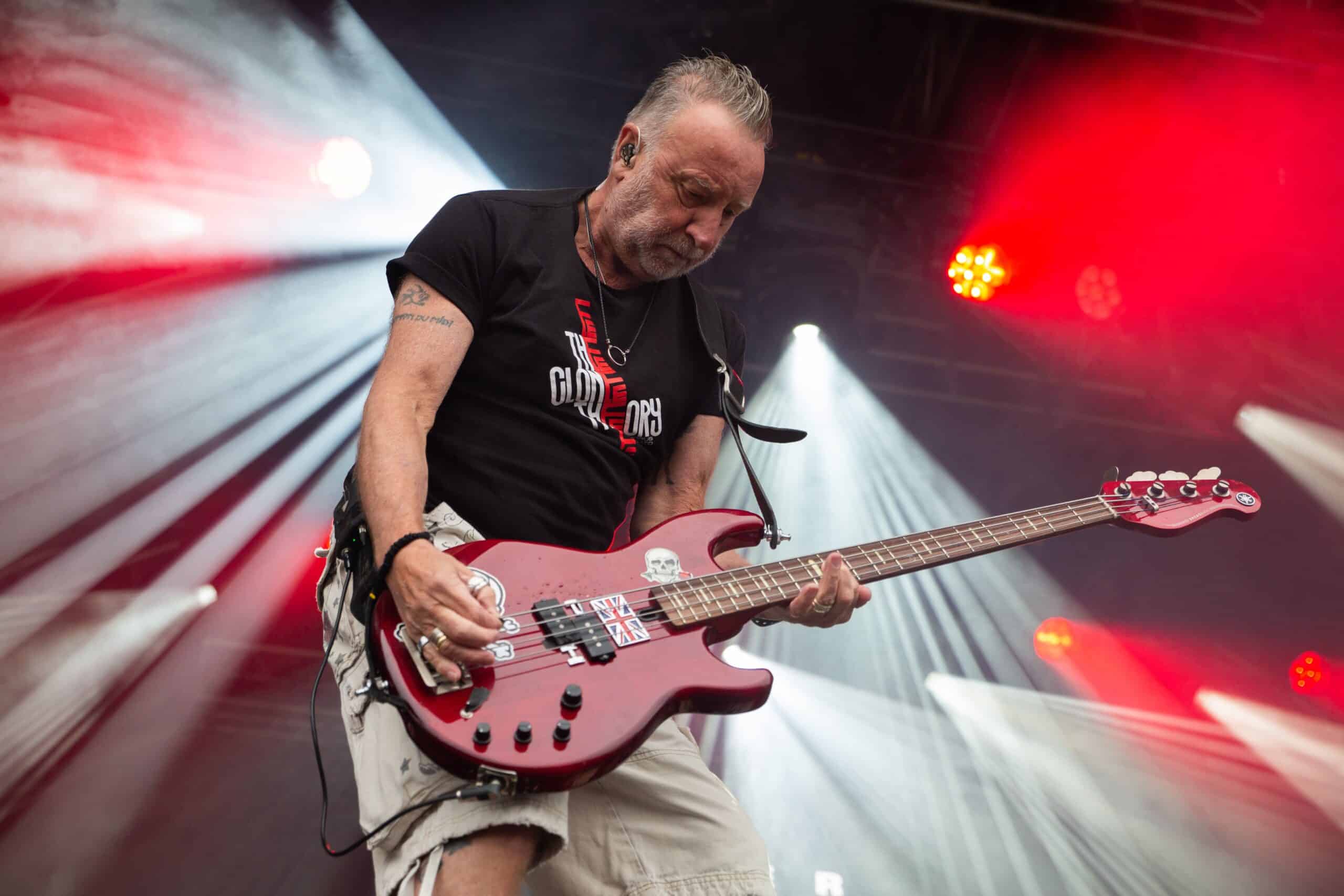

In September 2016, I attended my very first concert. Nervous and alone, I stood in the middle of a Manchester crowd that spanned all ages and subcultures. Peter Hook, co-founder and bassist of Joy Division and New Order, brought it all together. That night, Hook played an extensive setlist with both bands, closing with “Love Will Tear Us Apart.” After that, I was in the know; this special show would set the precedent for all the concerts that followed.

Peter Hook // Mark McNulty

True to their name, Peter Hook & The Light (formed in 2010) light up a catalogue gathering dust. With the colourful electronics of New Order came resistance to the band’s former life as Manchester’s finest post-punks. After finally splitting up in 2007, Hook sought to reverse this trend with The Light. Consequently, the atmosphere of their performances is pure celebration; from Ian Curtis to Tony Wilson, Rob Gretton to Martin Hannett, Factory folklore is brought to life.

Eight years after that night in Manchester, I have the pleasure of interviewing Hook for his current substance Tour. Through the window in front of me I can see the upper tiers of the York Barbican, where The Light will play in October. But more immediately the dreaded notification appears on my laptop screen:

“Peter Hook came into the waiting room.”

Shit.

Aside from the interviews, books and the music itself, I wonder if Hooky is as good as he seems. After all, I’m meeting a hero.

No worries. With his usual “Are you OK, mate?” and his defiant choice of clothing, or lack thereof, I soon felt at ease. The shirtless appearance has a good reason, mind you. Hook is swapping Manchester for Mallorca this week – a short but well-deserved break between tour dates.

Pleasantries follow and we move straight to the questions. I am curious how The Light is doing these days. In fact, Hook’s son and occasional bandmate Jack Bates has been

played bass for Smashing Pumpkins. “He’s doing a big tour with them right now opening for Green Day. Huge venues!” Jack will no doubt return, but for now he’s busy. Dave Potts is still around, though. The two have been working together since 1989, longer than Hook was working with Bernard Sumner and Stephen Morris. Between 1997 and 2000, he and Potts released two LPs under the name Monaco: Hook recalls:

“Of course, I then made the terrible mistake of returning to New Order. It was like returning to an old friend and realising what crap you hated about them from the start.”

From left to right: Stephen Morris, Peter Hook, Gillian Gilbert, Bernard Sumner.

For fans, the split plays out like a heated argument between mutual friends. While one hesitates to take sides, one understands their respective animosities. If there is one saving grace, however, it is the rise in Joy Division live performances. When The Light originally formed, Hook reckoned with a legion of older, diehard fans from back in the day. In reality, there were and are an abundance of young faces in the audience. Hook thanks an influential figure whose opinion he once questioned:

“Martin Hannett gave us the gift of longevity. I can say with certainty that without his production, your father might not have played Joy Division for you.”

In dealing with these younger fans, Hook is regularly confronted with the tricky question. “What was Ian (Curtis) like?” His answer is both down to earth and surreal. “Just like you, I tell them.” Hook’s memory of Curtis will sound familiar to fans; the “Boy, boy who enjoyed a few beers and a laugh, but was also a bookworm who read Burroughs and Gogol in his spare time. Reality and myth often blur, but suffice it to say that Curtis was mortal.

“He was 19 when I met him. He didn’t know what he wanted to do in life, he just started a band without really thinking about it other than banging out a few songs with friends.”

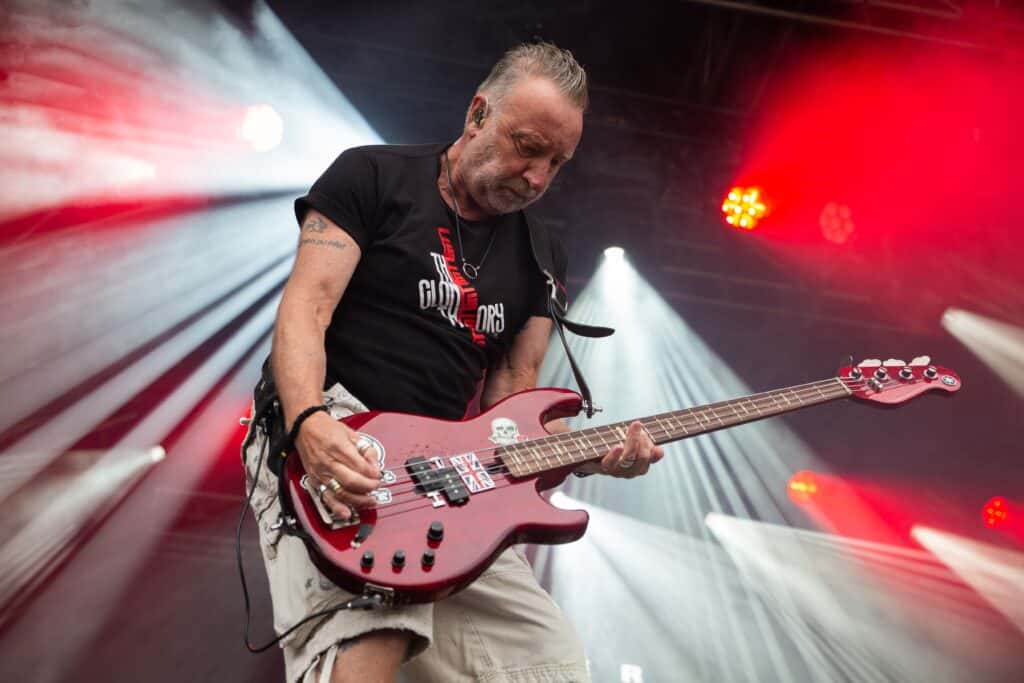

Peter Hook // Adam Kennedy

Curtis’ artistic work inspired future musicians from Henry Rollins To Daniel Brown. With his legacy in mind, Hook’s first Joy Division revival found him walking a fine line between tribute, reparation and “imitation,” as he himself put it. Rowetta (Happy Mondays) convinced him to sing because no one else had “the guts.” Fourteen years later, Hook has settled into his role as frontman and is ready to make a bold claim that might irritate the odd fan:

“The Light have been playing Joy Division for so long that it sounds like they actually wrote it. They play it so naturally and if you compare it, you’ll find that some parts of it are better than Joy Division, simply because they’re finished.”

For this reason, the band took a lot of time for substance. On the side of the New Order substance (1987) is a collection of pop hits that will put even the moodiest concertgoer in the mood. In contrast, Joy Division’s substance (1988) includes everything from early B-sides to iconic standalones. The material speaks to their prolific output in four short years, but ultimately lacks the polish of Unknown pleasures (1979) and Closer (1980).

“You still hear disagreements in the (substance) recordings. Back then, you didn’t have the money to re-record it, so you always captured a rough edge. 44 years later, you correct those little mistakes.”

The Light don’t want to usurp the original recordings; they’d rather reinterpret them with the same “heart and soul,” as Hook puts it. Headlining shows are epic love letters to a rich discography, often stretching over 150 minutes, with a little break between sets. “It’s pure indulgence on my part,” Hook admits, “but I really enjoy it.” The success of this format has translated into a notable change in audiences:

“The first time we played with New Order as The Light, all the Joy Division fans went to the bar. When we played with Joy Division, all the New Order fans went to the bar. Now they don’t move.”

Since 2010, The Light have played through both catalogues. This approach was inspired by a set of 54 songs at Ian’s local church in Macclesfield, where the band ran through every song Joy Division had recorded. I’m curious if Hook still has trouble with the material, and am reminded of this decades-old discussion:

“Joy Division’s stuff is very natural, very simple. New Order sounds like someone is missing, which I like in a way. Gillian (Gilbert) tried valiantly, but she could never replace Ian. The songs are good, but you have to put a lot of things together to balance that out. It’s like a table with wobbly legs. Joy Division was perfect and New Order always had a bit of a wobbly leg, but the songs are great.”

As with most breakups, the feelings on both sides are complex and often conflicting. In the space of five minutes, Hook can first describe creative differences (“I lost my bass lines at the bar!”) and then praise the result of Sumner’s stubbornness.

Tensions within the group, ecstatic club nights, sunny adventures on the edge of madness. The recording sessions on Ibiza were, to say the least, eventful. So much so that Hook initially resisted the memory of this time and the works created during it. Today, however, he speaks of Technology with awe: “‘Fine Time’ stands out, doesn’t it?” The acid house opener embodied the group’s changing dynamic. After a night of drinking, Sumner wrote the song “more or less on his own.” Hook woke the next morning to a mostly electronic track and fought tooth and nail for his brief but effective bass cameo. Today he can appreciate the end result.

Meanwhile, “Run” is the centerpiece of a unique anecdote that Hook seamlessly recalls:

“I was in Heaton Park with my kids a couple of years ago. A beautiful summer’s day. Do you remember how people used to walk around with boom boxes? This topless boy had one and it was blaring this amazing music. I thought, ‘My God, this is fantastic!’ I thought, ‘whooo is that??‘ Anyway, I ran over and grabbed him. I said, ‘Mate, mate, who are you playing?’ He pressed pause and said, ‘Truing school… it’s Technology.”

Decades later, Hook is ready to embrace everything; from a violent Joy Division track from their Warsaw days to a forgotten republic (1993) is profound, the passage of time has rejuvenated it. Restoring his relationship to the rest of his discography reminds Hook of an ideal that Rob Gretton lived by:

“When we complained to Rob about the money, he would turn around and say, ‘I gave you something that will last forever and you’re moaning about half a million pounds (…) You can’t buy an inheritance like that!'”

In fact, The Light 2024 has toured everywhere from Perth to São Paulo, Prague to Toronto. “In a funny way,” Hook admits, “Rob was right.” Equally inspiring to these adventures is a grounded mindset that has kept him working tirelessly over the years. Hook points to his upbringing and the work ethic it instilled in him:

“When I was 12, my mother would cut a piece of cardboard and put it in my shoe to cover the holes. When it rained, you were stuck (…) Maybe I worked too hard sometimes, because I don’t want to go back to that. That’s why my wife says I have so many pairs of shoes now, more shoes than I could ever wear!”

Now, at the age of 68, I am curious how Peter Hook would define success beyond his shoe rack. The question surprises him a little; he has had it easy so far. When asked this question, he thinks about his words before he speaks. “You can answer However you want,” I assure him. Ultimately, the answer lies somewhere in between Movement (1981) Songs that Hook sang: “Dreams Never End” and “Doubts Even Here”. I’ll leave the last words to Hooky:

“When I look at what I have – a beautiful wife, wonderful children – I consider that a success. I still have to work to earn a living, but I have plenty of shoes with, not without, holes in them, so I’m very happy about that. Success is really intangible. When I wake up in the morning, mate, that’s a success – I think, ‘Wow, another chance to mess it up!’.

I still have the same problems and doubts as everyone else in the world. I’ve learned that nobody is just one thing (…) I’m very proud of what I’ve achieved. For the others in New Odour, it was a little slip-up that probably still needs to be fixed, whether it’s Henry Kissinger or someone else, but yes, life is beautiful. Life is good.”

Watch and listen to the entire chat below: