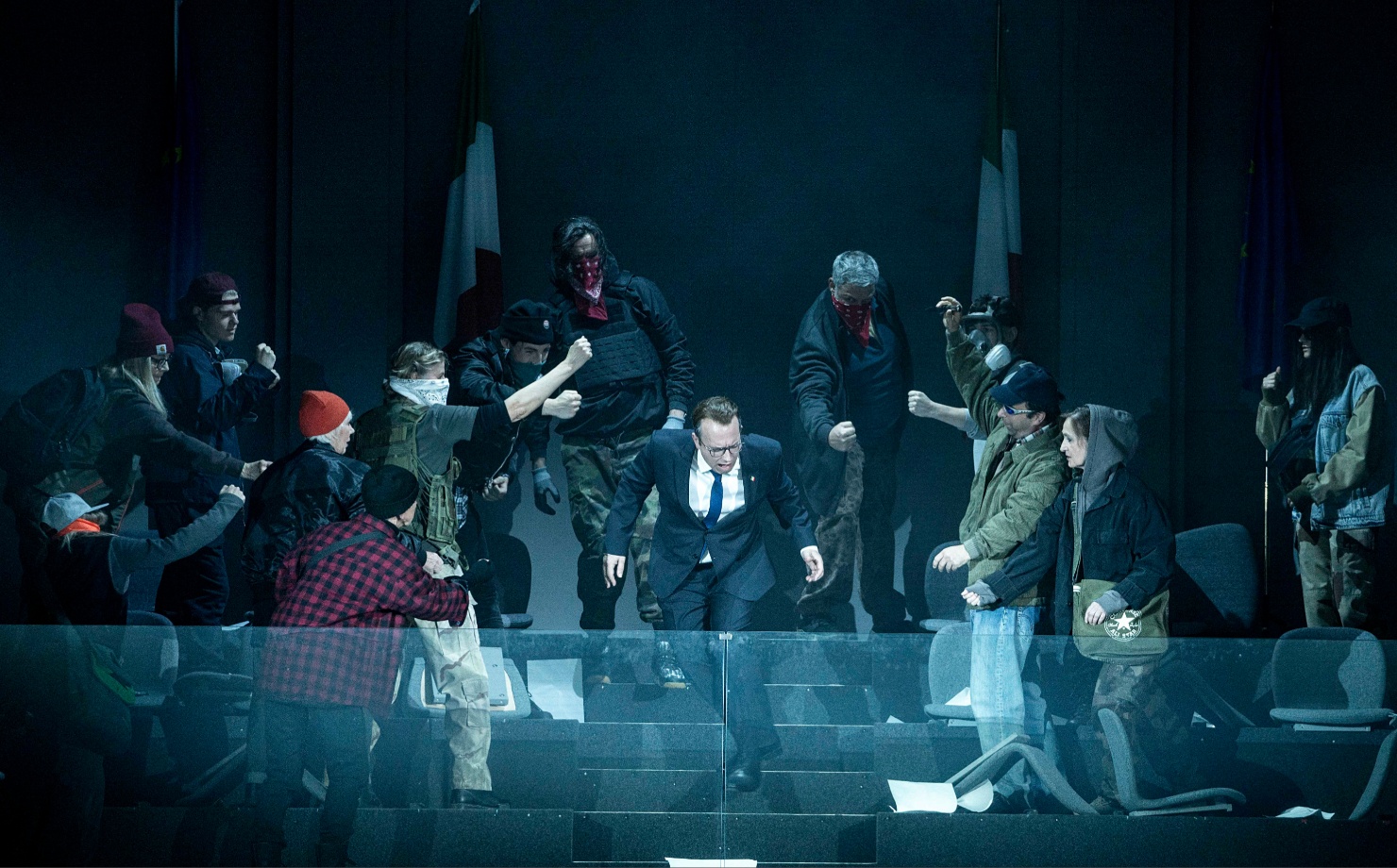

(Photo credit: © SF Marco Borrelli)

Can you be merciful to fascists? In Robert Carsen’s interpretation of Mozart’s “La clemenza di Tito,” the answer must be a clear “no” – otherwise they won’t miss the opportunity to stab you in the back the moment you turn your back on them.

Robert Carsen often enjoys updating operatic plots and making them reflections of current politics – often leading to quirky outcomes and thought-provoking responses. In doing so, he reveals the political messages that the past has to offer the present. “La Clemenza,” however, is a bitter pill to swallow. Composed in the aftermath of the French Revolution, the idea of ”grace” or “mercy” for those who might have been killed by King Leopold II’s cousins on the guillotine is a radical idea – albeit an appropriate message for the last days of absolutism.

Carsen reformulates the problem by asking: Should we show mercy on January 6?th Rioters? And he even expands it by making his Vitellia the personification of the Italian Giorgia Meloni. The question then becomes: can we be merciful – or perhaps simply enter into dialogue with the current right-wing movement? For Carsen, such a dialogue is impossible. In a surprising plot twist, Tito’s mercy leads to Meloni/Vitellia carrying out a second coup, this time successfully. As Maya Angelou once said, “When someone shows you who they are, believe them the first time.” And maybe a bit of Cobra Kai’s motto: “No mercy.”

On the surface, there is not much to criticise about Carsen’s interpretation. Why not update the plot? It is a matter of respecting certain differences. Mercy in the last days of the Ancien Régime is something very different from the current crises of democracy in the West – the regime is different, and the dispositif of mercy and forgiveness was an important form of politics, which is impossible in the current criminal justice system. Even the understanding of repentance and self-improvement in the 18th century seems to be completely different from today. We are convinced that some people are beyond redemption and should be punished for life if possible. But what would happen if we actively showed pitiful mercy to our oppressors?

Musical highlights

Gianluca Capuano conducted a Mozart full of edges: hard timbres and fairly punctuated sounds. Forget the Mozart of sublime sounds: here everything had to be wild and piercing. Although one could see the reason for this approach, which emphasized the aridity of current politics, its vivacity severely affected the singing and hardened many vocal lines. Nevertheless, the second act – not as musically interesting as the first – had a better tempo than usual. The riot scene also worked well under Capuano’s pounding baton.

It’s no secret that this “La Clemenza” was Cecilia Bartoli’s star vehicle. Although she had recorded Sesto earlier in her career, it’s surprising that this was the first time she had sung the role onstage. There’s something uncanny about listening to Bartoli today. No other singer has as much charisma and such obvious sympathy with the audience. She has been recording CDs since Luciano Pavarotti was in his prime. To attend one of her performances is to enter a musical world that belongs not only to the present but also to the past. Her highly recognizable voice and famous hyperarticulation — honored with her unique coloratura — tower above her. It’s hard to attend a Bartoli performance and not think of a voice that’s featured on so many albums.

A little prejudiced by Capuano’s harshness in the orchestra, Bartoli delivered a Sesto who is experienced and weary – still connected and entangled with Vitellia – but also a little discredited with himself. It was interesting to see such an energetic artist take on the role in such a nocturnal way. Her voice, brighter, less rounded, shone best in the pianissimi with a piercing articulation of the Italian consonants. Her “Parto” aria, surely a showstopper, blossomed when Capuano let Bartoli set the tempo – when she was on her knees, singing, almost praying, waiting to hear the basset clarinet solo.

The other star of the evening was undoubtedly Daniel Behle’s Tito. It is common to say that Tito is not the master of his own opera, but I was quite impressed with the way Behle embodied the most compassionate of democratic leaders. In the transition from autocracy to democracy, Tito was always keen to do everything fairly, to listen to everyone, and to acknowledge the complexity of power. In his first aria, “Del più sublime soglio,” Behle calmly managed to distinguish a long, languid emphasis on the word “sublime” with a wounding “tutto è tormento il resto.” The effect was precisely that of a thoughtful and perfectly understanding monarch. A similar situation occurred in his second aria, “Se all’impero,” but now with an even greater disdain for the consequences of his office – clearly a Tito under the sword of Damocles.

Further cast highlights

Alexandra Marcellier’s Giorgia Meloni/Vitellia was an interesting character. On the one hand, she is supposed to have a cocaine-like sex appeal; on the other, despite being a villain, she is supposed to seem capable of redemption (particularly through the power of a basset horn solo). Marcellier was acerbic, with an explosive and loud upper register for most of the opera. Her phrasing was full of edges, but her aggressiveness worked. Her redemption aria, “non più di fiori,” was interesting, although it bore few parallels to Sesto’s “Parto.” She offered a disingenuous delivery – a true achievement, given the opera’s twist.

Annio was sung by the lovely Anna Tetruashvili. Carsen’s decision to make Annio a woman had an interesting result: in retrospect, the revelation of Annio’s affection for Servilia felt almost like a coming out – and Tito’s reaction like a moment of acceptance. Although such a “coming out” is not so obvious, Tetruashvili’s sincerity was present when singing the role. Her lively voice seemed to harmonize well with Capuano’s vivacity.

Nevertheless, both Tetruashvili and Melissa Petit, as Servilia, used a little more vibrato than usual – partly due to the demands of the orchestra – but also in response to their attempt to sound more decisive in their requests and reactions to others.

Ildebrando D’Arcangelo seemed an almost luxurious choice for a coadjutant role like Publio. His immense vocal talent and charisma were evident in the rather short aria “tardi s’avvede”. His voice was firm and generous, with an imposing tone and a richness of sound that is similar to Mozart and is hard to find.

Ultimately, La Clemenza is a great provocation: showing mercy to those who once tried to kill us seems like an impossible demand. One could agree, however, that La Clemenza is not necessarily Mozart’s most inspiring work. In its core moments, especially in the arias with wind solos, there is a belief in a path of repentance to transformation that could sound like a perfect future utopia.