Color is one of the building blocks of art. Imagine all the new art that could be created if artists had a radically expanded palette at their disposal.

That’s what went through my mind when I first saw the book The Universe in 100 Colors: Strange and Wondrous Colors from Science and Naturea collaboration between science educator Terry Mudge and artist Tyler Thrasher, due out next month from Sasquatch Books.

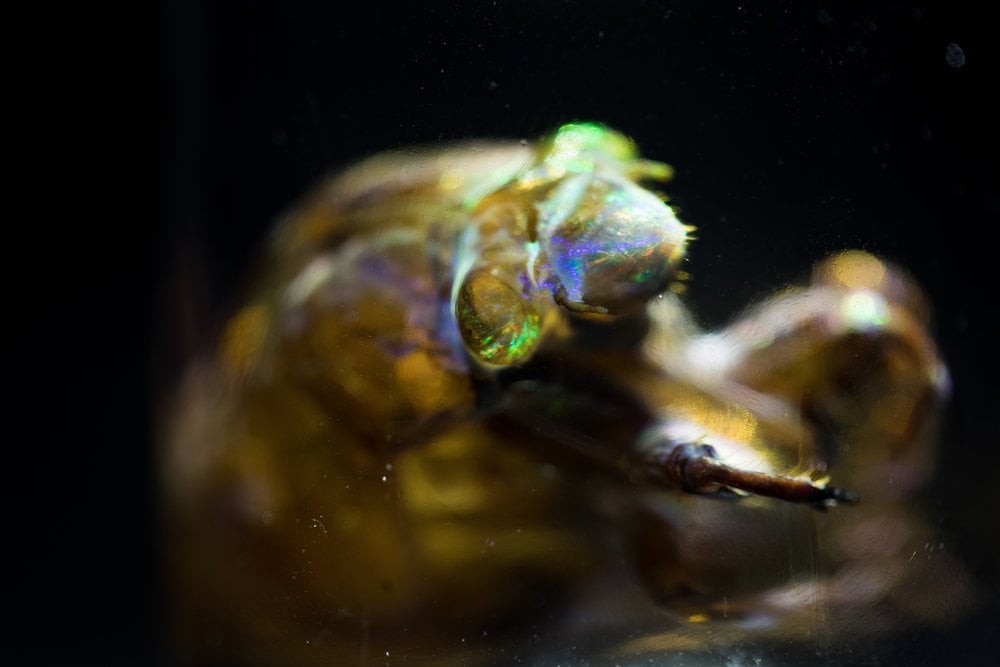

For Thrasher, who lives in Tulsa, Oklahoma, the starting point of the project was actually his own very unusual way of making art. After studying computer animation, he decided to pursue an artistic career. To that end, he spent years developing his own recipe for “growing” opals, the semi-precious stone known for its iridescent color, and using them to decorate everyday objects. In 2015, his series of opal-covered insects became popular on the internet and they remain one of his artistic trademarks (he also sells glowing flowers).

Tyler Thrasher, Opalized cicada shell (2021). Courtesy of Tyler Thrasher.

Thrasher’s opal studies also proved to be a gateway to a wider interest in the effects of color. “For me, opals embody the absolute magic of color,” he told me via Zoom. “You see this photonic spectacle that is out of this world, it feels like you’re staring into another universe – it’s hard not to fall in love with color when you’ve grown an opal.”

“Opal” receives an entry in The universe in 100 colors. The other entries range, quite literally, from the mundane to the cosmic, from “Landlord White” — the most commonly produced color in the world because its off-white hides dirt in a way that pure white cannot — to “Cosmic Latte,” a term astronomers use for the “eggnog-like color” that is the “average color of our observable universe.”

There are also colors that are rare and forgotten. Sometimes this is because their source has been lost, such as the “soft, reddish pink” of primordial chlorophyll, which scientists synthesized in 2015 from billion-year-old remains of microorganisms and which represents the “oldest scientifically documented pigment on Earth.” Sometimes this is because they are considered too toxic, such as oripigment, a royal orange used by Raphael and Bellini, among others, and today considered extremely dangerous due to its arsenic content.

Raphael, Sistine Madonna (ca. 1513–14), in which oripigment is used for the orange-coloured robes.

Other colors are the product of scientific experimentation or industry, such as Yinmn Blue, a recently synthesized ultrablue (my Artnet colleague Sarah Cascone helped popularize it). Or there is the wonderful sonoluminescence, an enigmatic high-frequency blue-violet created by the energy released by the explosive sound of small bubbles bursting under extreme experimental conditions. This discovery was made in 1934.

And there are colors that say something about perception itself, like intrinsic gray, which is what we see when there is no light at all—not black, but a “deep, dark, blurry gray.” As the book explains, intrinsic gray is “a color field our brain creates as a survival mechanism because it allows us to still perceive contrast when we need it,” so we can (hopefully) spot predators even against a pitch-black background.

Thrasher’s collaborator Mudge runs Matter, a subscription service that sends out a selection of cool educational science materials each month. It describes itself as a “science museum in a box.” The two were studio mates, and the idea of documenting the properties of the strange materials Mudge was assembling was one of the seeds of the book. Thrasher, for his part, combines artistic and scientific experimentation in his work, describing himself as “your personal mad scientist.”

The Universe in 100 Colors: Strange and Wondrous Colors from Science and Nature by Tyler Thrasher and Terry Mudge (Penguin Random House, 2024).

Rooted in their shared background in popular science, The universe in 100 colours is an excellent textbook that provides easy-to-understand explanations of the many complex factors that combine to create the experience we perceive as “color” – not just the properties of light or pigment, but also mental states and the molecular composition of surfaces. (The latter gives us what is known as “structural color,” an example of which is the “neat and tightly packed arrangement of silica nanoparticles” that give opals their special color properties.)

But most of all, the book is just a mind-expanding delight. It makes you as curious about seeing as it explains seeing scientifically – and that is the purpose of the book. “Putting it together has given me a deep appreciation for all the wonderful, magical things around us that we take for granted: the color of a butterfly chrysalis, the gold of gold,” Thrasher told me. “I hope it gives people a way to appreciate the seemingly mundane – which is very, very exciting indeed.”

Follow Artnet News on Facebook:

Want to stay up to date in the art world? Subscribe to our newsletter and receive breaking news, insightful interviews and astute critical views that drive the discussion forward.